Until the development of large, long range cannons, military and civil defence activity was mostly carried out on the surface. Combat took place in the open, wherever armies happened to find themselves in proximity, and took the form of skirmishes, charges and close quarter fighting. Towns were fortified with keeps, moats and ramparts where the besieged people spent most of the time awaiting relief from the rigours of isolation and starvation. Underground excavation was limited to dungeons, crypts and cellars, with the occasional sally port for a surprise attack or escape. The attackers occasionally attempted to undermine walls and battlements. Little of this underground activity has left any trace today.

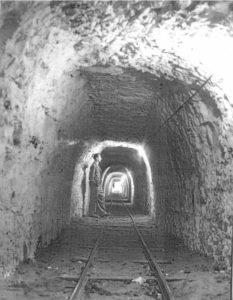

The development of the large cannon, which could batter walls and armies from afar with impunity, must have seemed at first the ultimate weapon. The effect, however, was to send the whole concept of defence below ground, from which it has not emerged since. The design of fortifications underwent radical change with the disappearance of keeps and ramparts, development concentrating on the moat. A substantial ditch was dug up to 60ft deep and 100ft across, which could not be readily filled or bridged. Excavated material was used to build up an inner mound and the lines of approach were levelled to provide a clear arc of fire. The walls of the moat were lined with bricks or masonry, many feet thick, and a network of tunnels installed to enable men to move quickly around the fortification. Firing slits were positioned to create maximum havoc upon the enemy, gun batteries were built and, wherever possible, natural obstacles such as cliffs or hills were incorporated.

Thus protected, an army could sit out a siege, dominate communications and harry the enemy. This remained the situation until 1940 when the fortress at Eben Email fell to a new ultimate weapon – attack from the air. The Kent coast has many such fortifications and they are largely ignored in guidebooks in favour of more visually appealing surface structures. They are, nevertheless, equally impressive in terms of the ingenuity of their construction and their place in military history, even though none were put to the ultimate military test.

Western Heights, Dover

Although Dover Castle dominates the town, on the other side of the valley there is a discreet but no less impressive set of fortifications known as the Western Heights. The construction work started in 1779 to counter invasion threats from the French and Dutch, work gathering momentum until 1814 when an armistice was signed. William Cobbett passed this way in 1823 on his ‘Rural Rides’ and commented ‘…a couple of square miles or so were hollowed out like a honeycomb, that either madness the most humiliating, or profligacy the most scandalous, must have been at work here for years’.

Despite such views, work soon began again with the threat of Napoleon Ill and the re-unification of Germany. The major works took place in 1850 and cost £300,000, which included removing the top of the hill and digging four miles of moats up to 60ft deep. The features are a maze of tunnels, cantilevered drawbridges, stairs, wells and firing positions. Although the features were connected by a continuous moat, they formed self-contained units that were capable of fighting on if part of the complex was overrun. The features are the Western Outworks, Citadel, Outer Bastion, North Centre Bastion and Drop Redoubt. The last two are now bisected by a road, for which the ditch has been filled in.

Another interesting feature is the Grand Shaft that was built in 1802 and connects the fortress with an entrance at the base of the cliff off Snargate Street. At the top, 59 steps lead down into a funnel shaped depression where the 20ft wide shaft descends for 100ft. It is brick lined and there are three interlocking but separate spiral staircases, lit by apertures into the shaft. At the bottom, they all converge to join a passage out to the street. it is said that one staircase was for officers and ladies, another for women and the other for soldiers. Obviously Victorian morals decreed that the three types should never meet up on dark stairways! The sites can sometimes be visited by arrangement with Dover Council but the Citadel cannot, being occupied by a Borstal Institution.

The Medway Forts

Following a Dutch raid in 1667, a ring of forts was built around the town to protect the naval dockyard and these were improved and added to during the Napoleonic Wars. Despite the enormous cost, they never saw a shot fired in anger and Chatham today is still dominated by the largest, called Fort Amherst. Of the others, several have been demolished but some still remain, albeit hidden amongst trees or houses. These forts were smaller versions of the Dover fortifications and, although they had underground features, the local rumours of linking tunnels are not true. Fort Bridgewood, Fort Clarence, Fort Delce, Fort Pitt and Fort Darland have been demolished although a few features may still be found. Fort Borstal, Fort Horsted, Fort Luton, Twydall Redoubt and Grange Redoubt still remain at the time of writing but permission must be obtained from the respective landowners before visits. The most impressive was Fort Amherst and, luckily for posterity, this has been preserved. It is open to the public and volunteers often dress up in period military uniform.

World War I

This marked a change in the pattern of warfare since the fighting took place in the trenches of France and Belgium, with no requirement for new fortifications in Britain. It did bring in a new development, however, whereby men of the Royal Engineers began to tunnel under the enemy trenches to lay explosive charges, hence the derivation of the word ‘mine’. The base depot of the Royal Engineers was at Chatham and the area was used to experiment with new techniques of mining, since the local sand and chalk was almost identical to conditions at the Front. Very few of these trial mines were recorded at the time and, although it is likely that many collapsed subsequently, some still turn up in surprising places. The latest example was discovered following a collapse in a Gillingham back garden in 1988.

During the construction of a roundabout at the junction of the A2 and A278 in Gillingham, a set of 6 galleries was found which had been unsuspected. They were found to be on three levels from 20-50ft below the surface, being dug as a model for mining operations under Hill 60 in France and the subsequent battle at Messines. Each gallery consisted of an entrance tunnel which led to six chambers, each 20ft wide x 30ft long x 7ft high. They were in a very dilapidated condition and had to be completely in-filled.

World War II and After

The threat of air attack made it vital for the military to site important installations underground and this was especially so in the South East. Bunkers were excavated for radar stations at places such as St Margaret’s Bay in Kent and Beachy Head in Sussex. A headquarters bunker was sited at a place called the Wilderness near Tunbridge Wells and a multi-level one underneath Dover Castle. Home Guard posts were sited underground at a number of places in 1940 and, when invasion seemed imminent, similar sites were constructed for small commando units. The latter were supposed to come out after the enemy had passed by and to engage in guerrilla warfare. One site still exists near Hollingbourne but is well hidden. It is highly likely that other undisclosed military installations exist in Kent and Sussex that are still regarded as military secrets.

Civilians also needed air raid shelters and large communal ones were made by adapting existing tunnel systems at Chatham, Rochester, Sevenoaks and Chislehurst. Perhaps the largest shelter in Britain was built in 1939 at Ramsgate, part of which adapted the existing tunnel of a scenic railway. The system was 4 miles long and encircled the whole town, with several entrances to allow the citizens to shelter quickly when the sirens sounded. The tunnels were divided into sections with dormitory facilities, each allocated to a specific street. There was electric light from the town supply and hurricane lamps as a back up. The only things forbidden were smoking, pets and perambulators. The system is still intact but was sealed up after the war, access being closely controlled by the local council. At the time of writing there is talk of opening it up again as a museum.